The last El Niño – from around April 2023 to May 2024 – was not only a long, but also strong event.

Sea surface temperatures (SST) in the Pacific Ocean waters off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru rose up to 2 degrees Celsius above the 30-year average for this region in some months. That was way higher than the minimum threshold, of 0.5 degrees Celsius or more positive SST departure from normal, for classification as an El Niño event.

The long and strong El Niño was responsible for large parts of India not getting adequate rainfall during the 2023-24 monsoon (June-September), post-monsoon (October-December) and winter (January-February) seasons. It was accompanied by the winter’s delayed onset and warmer-than-usual temperatures, culminating in the heat waves from the second half of March through mid-June 2024.

The end-result was 2023-24 turning out to be a not-so-great agricultural year, with subpar kharif (June-August sown and October-December harvested) as well as rabi (October-December sown and March-May harvested) crops.

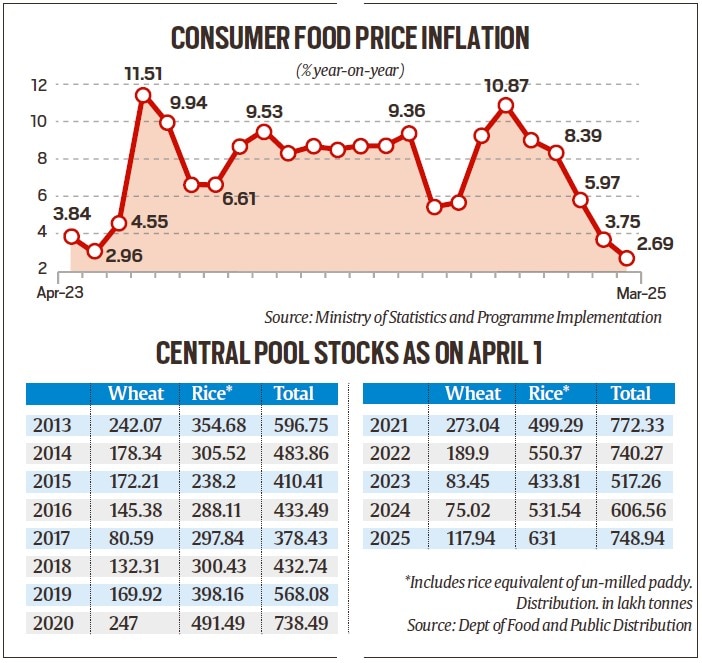

Its effects were also felt in food prices. The annual rise in the official consumer food price index averaged over 8.5% between July 2023 and December 2024. That made it one of the country’s longest episodes of food inflation in recent times.

High food prices, in turn, impacted consumer spending. With households having to allocate a larger portion of their incomes to food, they were left with less money to spend on other things. Hindustan Unilever, India’s largest fast-moving consumer goods company, reported annual sales volume growth of 2% each in the July-September 2023, October-December 2023 and January-March 2024 quarters, 4% in April-June 2024, 3% in July-September 2024 and 0% in October-December 2024.

Simply put, El Niño – an abnormal warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean waters, leading to enhanced evaporation and cloud-formation activity in western Latin America, the Caribbean and the US Gulf Coast, and correspondingly depriving Southeast Asia, Australia and India of convective currents – wreaked havoc on the country’s farm output, pushing up food prices and crimping household spending.

Thankfully, those pressures have subsided since the start of this calendar year. Retail food inflation was at 2.7% year-on-year in March (see chart), the lowest since November 2021.

The reason: An agriculture production recovery in 2024-25 on the back of a good monsoon, sans El Niño or other weather shocks.

If anything, there was a mild La Niña or a cooling of SSTs in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. La Niña does the opposite of El Niño: As the trade winds blowing west along the equator carry warm water from South America towards northern Australia and Indonesia, they cause increased cloudiness and rainfall over this region – whose effects may percolate to India too.

The SST departures from the average weren’t significant enough this time (minus 0.5-0.6 degrees during November-February 2024-25) to qualify as a full-fledged La Niña event. But it ensured a more or less normal winter – and a decent rabi crop, on top of the monsoon-aided kharif harvest. The softening of food inflation has coincided with their arrivals in the market.

The real relief would be in wheat, the stocks of which in government godowns – at 7.5 million tonnes (mt) on April 1, 2024 – were the lowest for this date since 2008.

The 2023-24 crop, harvested and marketed in April-June 2024, wasn’t good in central India, because of the winter’s late arrival followed by foggy weather and lack of sunshine in January. While yields in north and northwest India were above par, the poor harvests in Madhya Pradesh (MP), Gujarat and Maharashtra dragged down overall production.

As a result, wheat prices remained elevated all through last year and beyond, even as the new marketing season from April has opened with not-too-comfortable government stocks.

The good news is that the crop in central India has been bumper this time, thanks to no major temperature anomalies or fog/smog conditions. Yields in north and northwest India have been reported marginally lower than last year, but should still add up to a higher overall national production figure.

“When temperatures spiked briefly in February, it seemed that the crop would mature early for harvesting by early-April. But March was relatively cool, which allowed normal grain-filling and harvesting to happen from the second week of April. Last year, my yields were the best ever, at 27-28 quintals per acre. This year, it is 24-25 quintals,” said Pritam Singh, a progressive farmer from Urlana Khurd village of Haryana’s Panipat district.

The bumper wheat harvests of 2024 and 2025, especially in Punjab and Haryana, have been attributed to moderate weather and also the cultivation of new high-yielding varieties such as HD-3386, DW-327, PBW-826 and PBW-872. “These varieties have bolder grains. The average weight of thousand grains from them is 50-54 grams, as against 40-44 grams for the older varieties,” Singh claimed.

One indicator of a good crop is prices. Fair average quality wheat is trading in MP’s Dewas and Ujjain markets at Rs 2,400-2,500 per quintal, as against Rs 3,000-3,100 three months ago and the government’s minimum support price of Rs 2,425. Higher government procurement in the current marketing season should help bolster its wheat stocks, over and above the already-record levels of rice (see table).

The hope from softening food inflation Consumer food price inflations and central pool stocks as on April 1

Last week, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) forecast an “above normal” southwest monsoon, with rainfall during the upcoming season (June-September) likely at 105% of the long period average for this four-month period.

If the forecast materialises – the IMD expects ENSO-neutral conditions (i.e. neither El Niño nor La Niña) – that should enable a further cooling of food inflationary pressures.

Viewed along with falling global oil prices (Brent crude is ruling at below $68 per barrel, compared to $80 three months ago) and a weakening dollar (from 87.5 levels in February to Rs 85.4 now), it translates into a “positive terms of trade shock” for Indian households, firms and the government. All three can retain a larger part of their incomes/revenues that were previously being expended on costlier food and imported inputs or subsidy. The immediate boost could be to household consumption.

That may, to some extent, compensate for the shocks to exports and general economic uncertainty from US President Donald Trump’s tariff wars.